How do hands work?

Hands have a very delicate and complex structure. This gives muscles and joints in the hand a great range of movement and precision. The different forces are also distributed in the best possible way. Thanks to this structure, you can do a wide range of things with your hands, such as grip objects tightly and lift heavy weights, as well as guide a fine thread through the tiny eye of a needle.

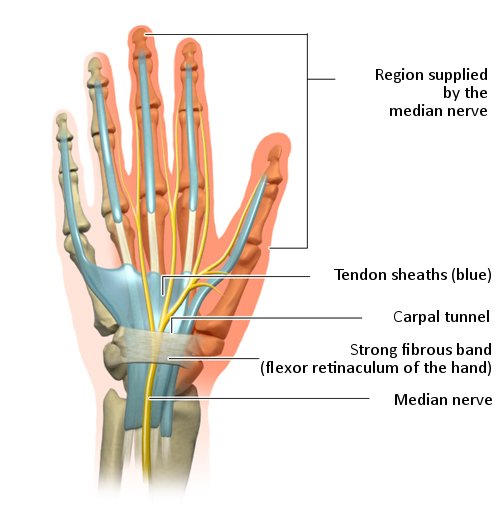

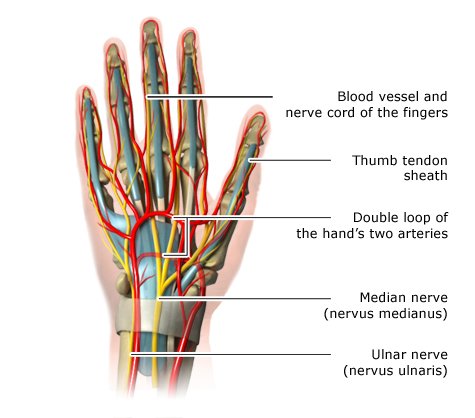

Hands are also quite vulnerable, though: Tendons, nerve fibers, blood vessels and fairly thin bones are all positioned right under the skin and are only protected by a thin layer of muscle and fat. Only the palm is protected by a strong pad of tendons (aponeurosis), enabling a powerful grip. Our hands are put through quite a lot every day, and often come into contact with potentially harmful tools. As a result, hand injuries and problems due to wear and tear are very common.

The right and left hand are each controlled by the opposite side of the brain. Usually one hand is preferred for carrying out fine and complex movements, so we often say people are either right-handed or left-handed.