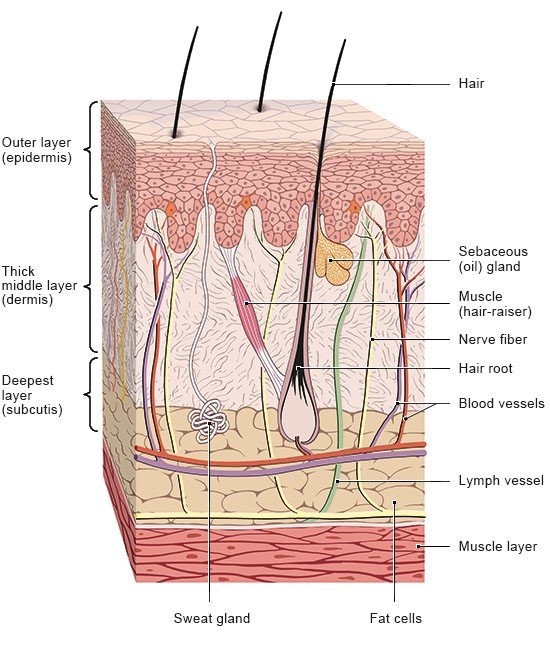

The skin is our central sensory organ, and it carries out a number of tasks. It is a stable but flexible outer covering that acts as barrier, protecting your body from harmful things in the outside world such as moisture, the cold and sun rays, as well as germs and toxic substances.

Skin also plays an important role in regulating your body temperature. It helps prevent dehydration and protects you from the negative effects of too much heat or cold. And it allows your body to feel sensations such as warmth, cold, pressure, itching and pain.

Skin also functions as a large storeroom for the body: The deepest layer of skin can store water, fat and metabolic products. And it produces hormones that are important for the whole body.

Just looking at someone’s skin can already tell you a lot – for instance, about their age and health. Changes in skin color or structure can be a sign of a medical condition. Regardless of their general skin type, people with too few red blood cells in their blood may look pale, and people who have hepatitis have yellowish skin. These changes may be less apparent in darker skin.

If skin is injured, the blood supply to the skin increases in order to deliver various substances to the wound so it is better protected from infections and can heal faster. Later on, new cells are produced to form new skin and blood vessels. Depending on how deep the wound is, it heals with or without a scar.

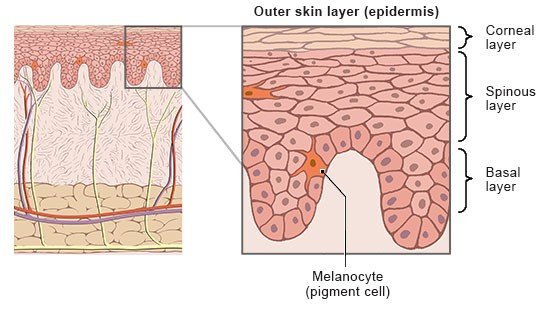

To be able to do all of these things, skin consists of three different layers: the outer layer (epidermis), the middle layer (dermis) and the deepest layer (subcutis).