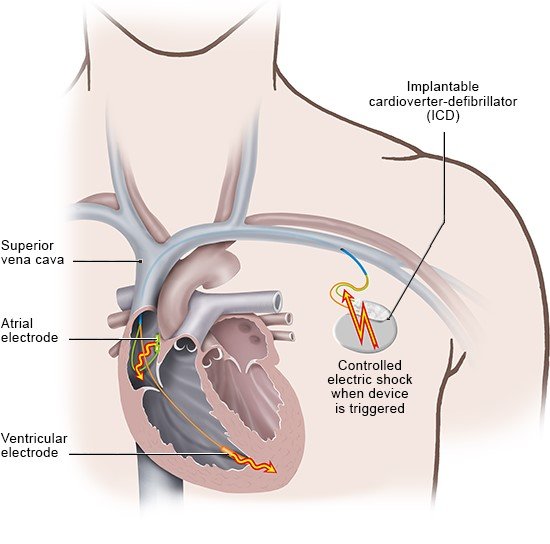

If you have a very abnormal heartbeat (arrhythmia) and your heart needs permanent protection, you can have a minor procedure to implant an ICD inside your body. The ICD is a disc-shaped device, about 5 centimeters in diameter. The procedure involves inserting the device under the skin of the collarbone and stitching it into place. Sometimes the doctor will insert it under the pectoral major muscle (the large chest muscle) instead.

Most ICDs have two wires known as "leads." The surgeon threads them into a nearby blood vessel and pushes them through to the heart. The leads enable the device to constantly monitor your heartbeat. Whenever necessary, it delivers several mild or single strong brief, controlled electric shocks. Sometimes special wireless devices are used.

If your heart suddenly starts beating too fast and there’s a high risk of complications, the device can send several shocks rapidly one after another. It does this to increase the heartbeat even more so that it can return to normal when the shocks stop. This is known as overdrive pacing.

Overdrive pacing doesn’t always help. If doesn’t work for ventricular fibrillation, for instance. In these cases, the ICD delivers one strong shock to stop the heart completely for a short amount of time. This is another way of getting the heart to start beating normally again. It sometimes takes several shocks for the heart rate to return to normal.

ICDs have built-in batteries that can last up to ten years, depending on the type of device. When they run out, the ICD has to be replaced. The leads stay in the body and are reconnected to the new device.

Some ICDs can keep a record of the heart’s activity. They do this in the form of an ECG, which they store and transfer direct to the doctor’s practice.