What are the stages of human growth?

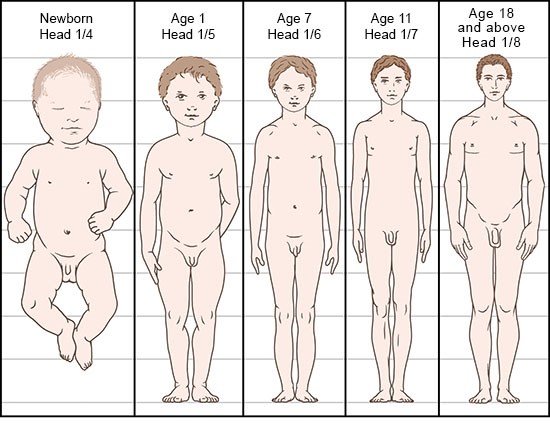

Humans start to grow straight after the egg is fertilized. This growth continues in the mother's womb until the embryo finally becomes a baby that is capable of living. After birth, the baby continues to grow, developing into a child, then a teenager, and finally an adult. During this process, their weight and height change. Their body proportions also change gradually. For instance, the head of a newborn is roughly one quarter of its entire height. The head of an adult is only one eighth of their height.

The shape of the body also changes little by little during the growth phase. There are times when it becomes heavier and times when it becomes taller.

The first weight gain phase happens between the ages of one and four. It is followed by a height gain phase, which lasts roughly until the age of eight. Then comes another weight gain phase up to the age of ten, again followed by a height gain phase, this time up to around the age of 15.

Afterwards, weight and height increase at the same time. This developmental stage is closely linked to the physical changes that occur in puberty. It ends earlier in girls than it does in boys. Girls’ bodies tend to finish growing when they’re around 16, compared to about age 19 in boys.