Bone structure

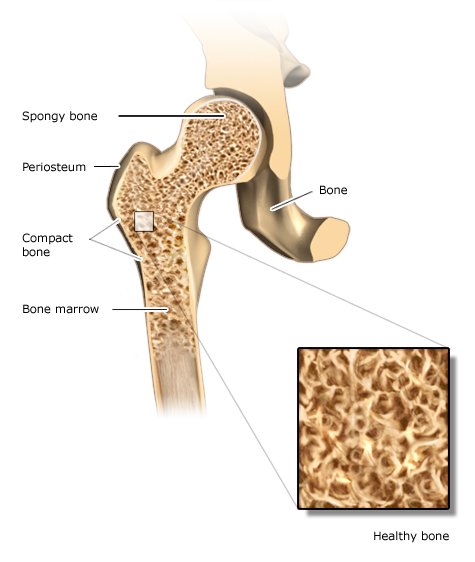

Our bones’ outer walls are referred to as the outer bone layer (compacta). This layer is hard and especially strong. Inside bones there is a supporting structure with interconnecting bony plates and rods called trabeculae. It is called spongy bone because of its sponge-like structure, but is sometimes also referred to as trabecular or cancellous bone. Long bones like the arms and legs also have a bone marrow cavity.

The bones have good blood circulation: Numerous veins pass through them. The spongy bone and the marrow cavities contain red bone marrow, which produces blood cells and what is known as fatty marrow from fat tissue. In childhood, many of our bones contain red bone marrow, but in adulthood red bone marrow is only found in certain bones like the ribs and vertebrae, the sternum (breastbone) and the pelvis.

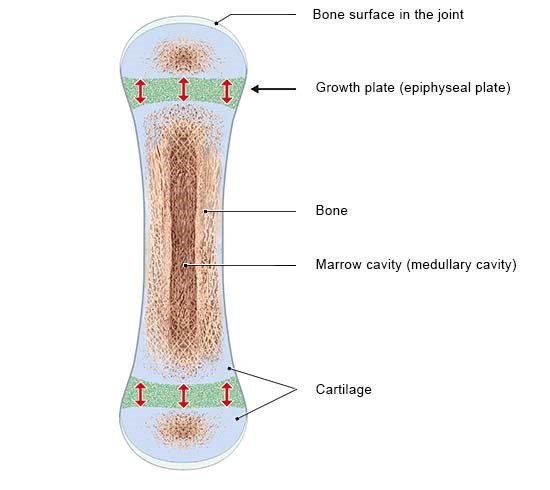

Some bones develop from connective tissue, like the skull. Others start off as cartilage that is later replaced by bone tissue. The arm and leg bones are examples of this. But they do not completely turn into bone for as long as we are still growing: A small amount of cartilage remains at the ends of the bones. These parts are called growth or epiphyseal plates. New cartilage is constantly being produced there, which later becomes bone. That allows the bones to keep growing longer. Towards the end of puberty, the growth plates gradually turn into bone as well, and our bones are fully grown.