Introduction

Abdominal pain is unpleasant, but it can happen from time to time in everyday life - for example, if you eat something that doesn't agree with you or you catch a stomach bug. This kind of pain usually passes quickly, and is not too severe.

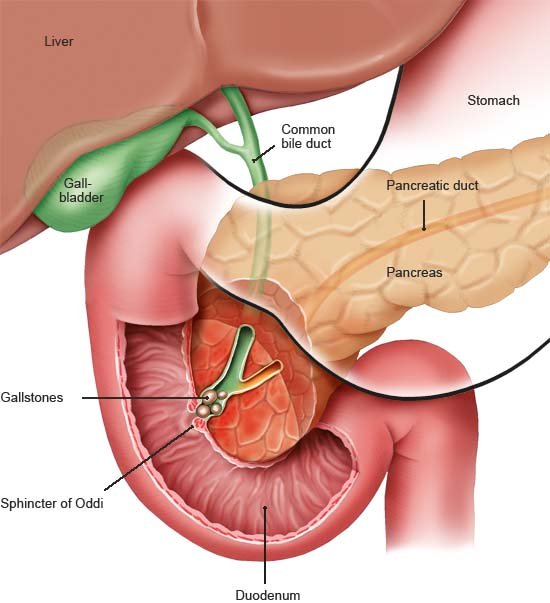

Sometimes, however, it is caused by a serious illness. The main signs of acute pancreatitis ( inflammation of the pancreas) are sudden and very severe pain in the upper abdomen. Pancreatitis is most commonly caused by gallstones or drinking too much alcohol.

The acute inflammation usually clears up after a week. But it may also lead to complications and other illnesses. If that happens, treatment can take several months.

Pancreatitis is treated in a hospital because it may become life-threatening if the complications get much worse.