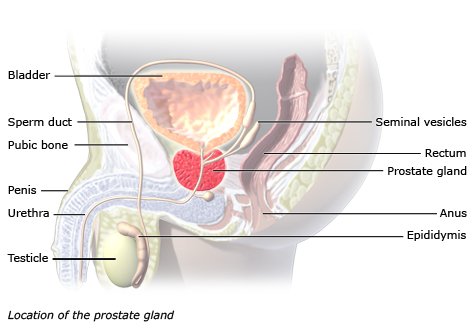

The prostate gland is surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue containing many smooth muscle fibers and elastic connective tissue, which is why it feels very elastic to the touch when it is examined. There are also many smooth muscle cells inside of the prostate. During ejaculation these muscle cells contract and forcefully press the fluid that has been stored in the prostate out into the urethra. This causes the fluid and the sperm cells, together with fluid from other glands, to combine to form semen, which is then released.

The tissue of the prostate gland can be divided into three different zones, listed here from innermost to outermost, which encircle the urethra like layers of an onion:

- The transition zone is found on the inside of the gland and is the smallest part of the prostate (about 10%). It surrounds the urethra between the bladder and the upper third of the urethra.

- The central zone surrounds the transition zone and makes up about one quarter of the prostate’s total mass. This is where the duct common to the prostate, seminal duct and the seminal vesicles is found. This duct is also known as the ejaculatory duct (Ductus ejaculatorius).

- The peripheral zone represents the main part of the prostate gland – about 70% of the tissue mass is part of the peripheral zone.

The transition zone tissue tends to undergo benign (non-cancerous) growth in old age.The medical term for this is benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). If this tissue presses against the bladder and the urethra, it can lead to difficulties urinating. This is a common problem among older men. Malignant (cancerous) tumors in the prostate mostly develop in the peripheral zone instead.

The prostate has various functions:

Production of fluid for semen:

- One part of the semen is produced in the prostate. Together with sperm cells from the testicles, fluid from the seminal vesicle and the secretions released by another pea-sized gland below the prostate (the bulbourethral gland), the prostate fluid makes up the semen. All of these fluids are mixed together in the urethra.

- The prostatic secretion is important for the proper functioning of the sperm cells, and therefore also for fertility in men. The thin, milky liquid contains many enzymes such as the prostate-specific antigen (PSA). This enzyme makes the semen thinner.

- The hormone-like substance spermine mostly ensures sperm cell motility (ability to move).

Closing of the urethra up to the bladder during ejaculation: During ejaculation the prostate and the bladder’s sphincter muscle close the urethra up to the bladder to prevent semen from entering the bladder.

Closing of the seminal ducts during urination: During urination the central zone muscles close the prostate’s ducts so that urine cannot enter.

Hormone metabolism: In the prostate the male sex hormone testosterone is transformed to a biologically active form, DHT (dihydrotestosterone).